In February 2024, when Universal Music Group (UMG) confirmed its acquisition of a majority stake in Nigeria’s Mavin Records, it was easy to see it as just another music industry merger—a business-as-usual transaction between capital and creativity. But this was no routine acquisition. This was a tectonic shift in how African culture is valued, owned, and projected into the world.

The Mavin deal is arguably the most important music sale to ever come out of Africa—not because of the dollars involved, but because of what it signals for African soft power, for creative sovereignty, and for the future of global storytelling.

Don Jazzy Didn’t Just Build a Label. He Built a System.

Founded in 2012 by Michael Collins Ajereh—Don Jazzy to the world—Mavin Records was not an overnight success. It was born from the ashes of Mo’Hits Records and built with grit in the chaos of an undercapitalized Nigerian music scene.

But Mavin did what very few African music entities had done before: it scaled without selling its soul. Over the past decade, it developed a fully-fledged ecosystem—from A&R and artist development to in-house production, marketing, digital strategy, even content studios. Mavin became a music label that functioned like a Silicon Valley startup: small team, big vision, rigorous execution.

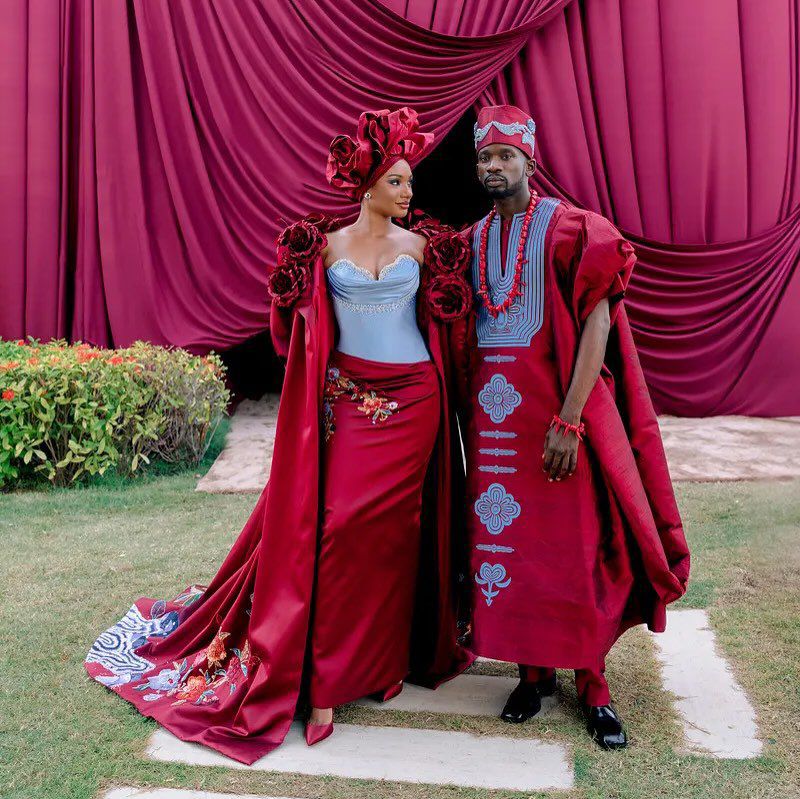

Its roster today reads like a syllabus in contemporary Afropop: Rema, the genre’s global wonderkid; Ayra Starr, the new face of Gen Z African womanhood; Ladipoe, Johnny Drille, Crayon, Magixx—each with a distinct brand voice, each emerging from the same machine.

This wasn’t luck. It was infrastructure.

Rema Broke the Ceiling. The Industry Paid Attention.

In 2023, Rema’s Calm Down remix with Selena Gomez became the highest-charting African song in Billboard Hot 100 history, peaking at No. 3. It spent over 52 weeks on the chart, crossed 1 billion streams on Spotify, and became a cultural fixture on every major global music platform. Ayra Starr wasn’t far behind: her hit Rush earned Nigeria its first-ever nomination in the newly minted Best African Music Performance category at the Grammys.

By late 2023, Mavin’s valuation had quietly ballooned to somewhere between $150 million and $200 million, according to multiple industry insiders. But these artists weren’t just racking up stats. They were rewriting what it means to export African music. This wasn’t just Afrobeats going global. It was the global market bending toward an African logic of sound, identity, and storytelling.

Institutional Capital Met Cultural Vision

The UMG deal didn’t come out of nowhere. In 2019, Kupanda Holdings—a joint venture between American private equity firm TPG Growth and advisory firm Kupanda Capital—invested in Mavin. The goal? Turn it into a scalable, globally competitive music company. The initial raise was $5 million at a modest valuation of $9.5 million. Over five years, that investment became one of the most successful African creative exits in modern history.

This deal closed the loop on a rare phenomenon in African media: private capital entering early, staying long enough to scale, and exiting without wreckage. In a continent littered with the bones of abandoned VC-backed tech startups, Mavin built slowly, carefully, and profitably.

That is why the UMG acquisition isn’t just a success for Mavin. It’s a proof of concept for the entire African creative economy.

A New Model for Cultural Sovereignty

What makes this deal even more remarkable is that Don Jazzy and Mavin’s COO, Tega Oghenejobo, retain operational control. Mavin is not being folded into a U.S. subsidiary. It’s being backed—not absorbed. The label will continue to run independently out of Lagos, with its own pipeline of artists, its own creative philosophy, and its own pan-African touring and marketing strategy.

This matters. For decades, African culture has been “discovered” by outsiders, mined for its aesthetic value, then repackaged and sold back with foreign imprimatur. This deal offers a different model: African leadership, global distribution. Local vision, institutional scale.

It also places Mavin at the center of a broader global pivot. As U.S. influence wanes in many parts of the world, the Biden administration has ramped up initiatives like Prosper Africa, designed to deepen trade and investment ties on the continent—not just in commodities, but in content. Cultural capital is the new oil. And Nigeria is brimming with it.

The Cultural Infrastructure Layer

But what makes Mavin unique—what made it valuable enough for UMG to pursue—isn’t just its artists or its hits. It’s its infrastructure.

Beyond music, Mavin has made smart bets on multimedia. Its in-house creative studio has already produced branded short films. It’s run regional artist development programs. It’s collaborated with platforms like Trace and HustleSasa to build pan-African touring circuits. It has begun to shape not just how African music is made, but how it’s distributed, monetized, and lived.

This is what Don Jazzy has built: a vertically integrated African culture company that understands scale but refuses to flatten culture. It speaks Gen Z, it speaks brands, it speaks Lagos and London with equal fluency.

Mavin isn’t just a label. It’s a template.

The Broader Shift: Afrobeats as Soft Power

To understand the true significance of this deal, one has to widen the lens.

Afrobeats has become a globally resonant artform not just because it sounds good, but because it signals something. It tells a new story about Africa—about joy, futurism, and cultural ownership. It travels across borders without translation. It gets danced to in São Paulo, lip-synced in Jakarta, remixed in Atlanta.

In 2022, Spotify reported over 13 billion Afrobeats streams, with Sub-Saharan Africa showing the highest year-on-year growth globally in recorded music consumption. Afrobeats is now a geopolitical export.

This isn’t just entertainment. It’s cultural diplomacy.

Why This Deal Changes Everything

The Mavin–UMG acquisition changes five things at once:

1. It affirms that African creative businesses can command global capital on their own terms.

2. It gives African artists a route to global careers without having to emigrate.

3. It proves that early-stage investment in African culture can lead to profitable exits.

4. It decentralizes global pop music—from L.A., London, and Seoul to Lagos.

5. It builds African cultural infrastructure from within—not as charity, but as industry.

Other labels will follow. Investors will follow. The next generation of African creatives will grow up in a world where Mavin showed them the road.

The Real Win: A Future That Feels Familiar

In the end, this isn’t a story about UMG. It’s a story about Don Jazzy. A former beatmaker who turned into a mogul by building a label that feels human, warm, rooted. A label that could have sold out a long time ago—but chose to build instead.

It’s about an African company that proved it could play in the big leagues without shedding its skin. That scaled culture, not just content. That saw the long game.

In a global economy increasingly driven by identity, authenticity, and story—Mavin sold not just music, but meaning. And in doing so, it opened the door not just for African artists, but for African ideas.

This isn’t just the biggest deal in African music. It might be the beginning of the next African century.