They say statistics are like a bikini, what they reveal is very suggestive but what they conceal is even more vital.

Nigeria, I fear, is in grave danger of becoming a serious country when it comes to data gathering and reporting. Exhibit A: Dr. Yemi Kale, Nigeria’s Statistician General in charge of the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

You may recall him as the man who broke ranks last year by declaring that the agency’s data had found that the number of Nigerians living in absolute poverty had increased by 6 percentage points from 2004 to 2010. This is strange as we would normally expect the government to lie about such figures. Or perhaps, the NBS was engaging in a practice known as ‘kitchen sinking’ i.e. throwing out all the bad news at once so that anything that comes after looks really good? Let us not be too cynical as there’s evidence that the NBS is doing some really commendable work.

Yesterday we were inundated with news about how Nigeria’s inflation was now 9%, the first time in 5 years we have hit single digit inflation figure. This has been the CBN Governor’s target (single digit inflation) for a while now so I suspect the man must be delighted at the news. But what does this all mean?

Normally we would rely on newspapers to translate statistical jargon into plain English for us but alas, our newspapers are either regurgitating, word for word, what NBS said in their report (BusinessDay) or completely, perhaps mischievously, misinterpreting the information (Punch).

First of all, since we are all learners, we need to go down low to the method used in calculating these numbers (I’m sorry, I won’t do it again).

The NBS uses a ‘basket’ of goods to calculate the CPI. This is not a real basket (or is it?) but an attempt to replicate, as closely as possible, the things that ordinary Nigerians buy regularly with their money. The point of this is to track how prices of the same goods are increasing over time. This tracking can, among other things, influence monetary policy e.g. if prices are increasing too quickly, the CBN might take the view that this is caused by too much money in circulation and will then increase interest rates to make it harder for people to spend money ‘anyhow’. Here in the UK, inflation numbers are used to determine a whole range of things from the annual increase in train ticket prices to salary increases. So if inflation is 9% and average salary increases in the same period was 5%, then we know we have a problem as people are getting poorer effectively.

So yesterday the NBS told us:

The composite Consumer Price Index (CPI) which measures inflation rose to 9.0 per cent year-on-year In January (compared to 12.0 per cent in December).

This was the highlight of what was reported. Let’s unpack it on a point by point basis.

1. The NBS uses 2009 as its ‘base year’. Because this is an index, what this means is that the numbers are incremental from 2009. For example, we can assume that a tube of Close-Up toothpaste was in the original basket in 2009. Let’s say at that time it cost N50. In the index, this will be given a value of 100. If the NBS then went to the market in 2010 (they actually do) and found that the same toothpaste had gone up to N55 i.e. a 10% increase, the index then becomes 110, a 10% increase.

2. There are 740 different items – some physical goods, some services – in the CPI basket. That is to say the NBS goes to the market to check the prices of these goods every month. There is bread in the basket, there is wine there. There is also repair of clothing (obioma) and of course petrol as well as dental services and hotel accommodation. You get the gist – they try to gather as much price information as possible.

3. Now most people buy Agege bread every week but don’t repair their shoes or clothes every week. They buy vegetables, yams, potatoes and ‘soft’ drinks also very regularly but can go 2 or 3 years without needing to sleep in a hotel room, yet all of these items are in the same basket. What to do? There used to be a French Economist and Statistician named Etienne Laspeyres who died in 1913. Mercifully, before he left this world he came up with a way of calculating a price index that is now known as the Laspeyres Index. If you do not know what this index means or the formula behind it, I promise you, a single strand of hair will not be removed from your body. But if you insist, it is here.

The NBS uses Laspeyres Index to calculate Nigeria’s CPI. In other words it uses a globally accepted standard. There are other methods used by different countries but Laspeyres is very much mainstream.

As stated above, some items are purchased more often than others and as such have more of an impact on the wallet than others e.g. petrol more than shoe repairs. So weightings have to be applied such that some items in the basket carry more weight than others to reflect as closely as possible what Nigerians are spending their money on. Again, for example, we can say that if people buy bread once a week but buy petrol once a month, we will give bread a weighting 4 times higher than petrol etc.

Perhaps I have missed it but I cannot find the overall weighting used by the NBS but I am told by several people that food items account for 60% of the weight of the basket. This makes sense – we have a lot of poor people in the country and a feature of poverty is a lack of disposable income to attend a concert featuring Kim Kardashian. Food comes first.

4. To make things even more complex, there is plenty of price distortion and information asymmetry in Nigeria – the price of bread will vary even within a state like Lagos and there really isn’t any readily available way for someone in Lekki to know how much it is sold in Ojodu. Before we then move to other states and start to get all sorts of wildly different prices for the same products. What this means is that NBS cannot sit in Abuja or Lagos and collect prices then tell us inflation is x percent. To arrive at a single inflation figure that will be credible, we need to gather as much information about it as possible.

Thankfully, the NBS seems to have risen to this challenge. It reports that every month 10,534 informants across the 36 states of the federation and Abuja send it around 3,774 prices on various items. Whereas a UK statistician can simply go to Tesco or even online to obtain prices, the job of the Nigerian statistician is infinitely harder and more open to errors due to this manual process of data gathering. But this is far better than pulling numbers out of their behind.

5. We are nearly there. Apart from obtaining prices on a state by state basis, the NBS also splits them into urban and rural prices based on population figures. So the urban prices carry a 46% weight inside the basket while rural prices carry 54%. This is broadly in line with the 2006 census figures per Nigeria’s population distribution.

There is also a split between a Farm Produce Index (basically raw food prices) and a Core Index (stuff that’s been processed), but we can get away with not worrying about this.

So now we have a fairly rough idea of the plumbing underneath the NBS’ headline inflation figures. We can thus interpret the 9% figure better. Again let’s do it on a point by point basis.

1. In January 2013, the CPI rose by 9% on a year on year basis. What this means is that when the NBS compared the prices of the items in the basket in January 2012 to the prices it obtained from those informants in January 2013, it found that overall, the basket was 9% more expensive this year than last year. Please note that we are only comparing January 2012 to January 2013 and not anything that might have happened in between.

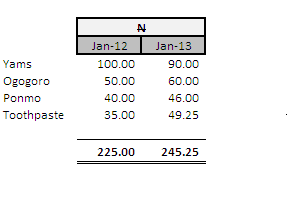

Imagine a chap named Faye (yes it’s a girl’s name but for this example it will have to be a guy). Faye only buys 4 items every month when he goes to the market – Yams, Ogogoro, Ponmo and Toothpaste. He also manages to stay sober enough to record the prices he pays for those 4 items every month when he goes to the market. This is what he recorded for January 2012 and January 2013

2. So is this 9% inflation increase year on year a good or a bad thing? It depends.Compared to January last year, Yams have dropped by 10% in price but sadly his beloved Ogogoro and Ponmo as well as toothpaste have all gone up in price. The total effect of what has happened to him – assuming his salary has not increased – is that he is now paying 9% more for the same things compared to a year ago. There might have been a Ponmo glut in the market in June 2012 which caused the prices to drop to N20 but Faye didn’t stock up then, so in January 2013 that is irrelevant to him.

Undoubtedly, a single digit inflation rate is much better than a double digit one. There is no debate about this. But the NBS also remind us of what happened in January 2012 – fuel subsidy was removed and in the confusion, prices went up arbitrarily as everyone from bus drivers to market women tried to protect themselves from the price shock. There was also a strike which paralysed businesses meaning that scarcity would have also caused prices to go up. The most important thing to note here is that what happened last January was not normal. In fact January is generally known to be a ‘broke’ month – everyone is coming down from the high of Christmas and New Year spending and the IJGBs (I Just Got Backs aka returnees) would also have left the country with their inflationary pounds and dollars. So we would expect prices in January to be restrained in a normal January.

Unfortunately, as impressive as they are, this is where the NBS numbers stop making sense at least to me.

According to them, prices in January 2010 were 12.6% higher compared to January 2009. In January 2011, prices were 12.1% higher compared to January 2010. In January 2012 – this is the crucial one – prices were 10.9% higher than January 2011 and of course in January 2013 they were 9%.

Let’s go back to what NBS said in their report yesterday;

The relative moderation of the Headline index from 12.0 in December to 9.0 in January could be largely attributed to base effects- These are as a result of higher price levels in the previous year, which imply that the year-on-year changes exhibited this year will be muted. In particular, the Nigerian economy exhibited several shocks in January 2012. The partial repeal of the Premium Motor Spirit (Petrol) subsidy led to increases in transportation costs as well as secondary effects, as the transportation costs affected both food and non-food prices. There were also the civil protests which followed, and the man-made price gouging during the month, as merchants tried to take advantage of temporary shortages.

The NBS are telling us that the reason for the 9% rise – the first single digit rise we have seen in 5 years – was that January 2012 prices were already very high due to those abnormal shocks the economy witnessed. Fair enough. But why is this shock not reflected in January 2012? From the figures I quoted above, you can see that when January 2012 was compared to January 2011, the increase was only 10.9%, certainly not the sign of a shocked economy anywhere. Or were the January 2012 numbers wrong? Did the methodology change? (I suspect this is the answer). You cannot say on the one hand that inflation in January 2013 was single digit because a lot of pain was frontloaded in January 2012 and then present figures that do not show the slightest hint of any pain for January 2012.

Interestingly, prices in December 2012 were 12% higher when compared to December 2011. In turn, December 2011 was 10.8% higher when compared to December 2010. This even makes more sense as a ‘shocked’ economy than the January figures and we know for a fact that fuel subsidy didn’t go until January. Was the economy ‘shocking’ in anticipation?

It is possible that the economy is now more stable. It is possible that this stability has allowed people to worry less about the future and as a result, the kind of anxiety that might normally cause prices to go up in Nigeria is now reduced. This is a good enough reason for inflation to slow down and in fairness to the NBS they do use the word ‘could’ implying that there were other factors at play.

As I stated earlier, I also strongly believe that the methodology or weighting of the basket has been changed in the last year which is probably responsible for the fall in the CPI. Regardless, these figures will be useless if there is no consistency over time. And if the NBS are telling us one thing and the numbers are saying another, then it would be hard to place any confidence in their numbers which is the entire point of the whole exercise.

They say statistics are like a bikini, what they reveal is very suggestive but what they conceal is even more vital.

Update: The NBS figures are even more normal than I thought. In looking at the numbers I missed out something – the movement between December 2011 and January 2012 is indeed abnormal (+2.29%) reflecting the subsidy removal.

It remains interesting that even though prices shot up in January, according to the NBS figures, they never came down from this artificial high…they simply stayed there and then climbed slower throughout the year. In 2011 for example, prices came down by 0.54% in April while in 2010 we had 2 months when prices came down. But we never witnessed any such come down in 2012. Admittedly petrol didn’t go back to the original N65 but I would have expected a contraction at least in one month after the knee jerk reaction to the subsidy removal.

Does this prove the point that when prices go up in Nigeria they never come down?

————————-

Op-ed pieces and contributions are the opinions of the writers only and do not represent the opinions of Y!/YNaija.

Kudos Dr kale