kakonomics

kækəˈnɒmɪks,ɛk-/

noun

- the strange preference for low quality outcomes.

- the word for ‘Nigerians are mad’.

“Nigerians are mad.”

Sound familiar?

How about: “Nigeria is special. Standard laws of economics don’t apply here.”

Or: “We have a unique system of doing things, that’s why we need homegrown solutions.”

I tend to roll my eyes or quickly get defensive when I hear such things. I’ve never been comfortable with the wisdom of the need for a collective lobotomy as the starting point for Nigerian economic policy.

But, ladies and gentlemen, it looks like they might be on to fragments of something. That said, we are not, in fact, mad.

#ChangeBeginsWithMe

#ChangeBeginsWithMeOur seeming national preference for low-quality outcomes, while clearly not ideal, isn’t ‘unique’, it’s quite rational.

It’s Kakonomics.

I kid you not. I didn’t make that up. Kakonomics is a real word, and you and I are right in the thick of it.

I came across this article by Tim Harford, The Undercover Economist. It’s called‘The Hazards Of A World Where Mediocrity Rules’, and describes completely familiar economic outcomes that possibly only apply (at a macro level) to a handful of countries, including definitely Nigeria.

I’m intrigued and excited, because finally (!) I have something other than raw emotion at my disposal the next time my skin bristles at the suggestion that something is fundamentally wrong with the psyche of individual Nigerians or that we are somehow cut from a deficient cloth.

I can now discuss, far more eloquently, why I am uncomfortable with the thrust of the Change Begins With Me campaign, which I think it is insidous by sermonising, without addressing context/system-wide issues.

But I digress.

‘Kakonomics’? Explain.

Happy to.

You know how people say “Nigerians are the Italians of Africa”? Well, now there’s a concept in behavioural economics to back it up. Tim’s article is actually based on the published work of a philosopher, Gloria Origgi, and a sociologist, Diego Gambetta, both Italian.

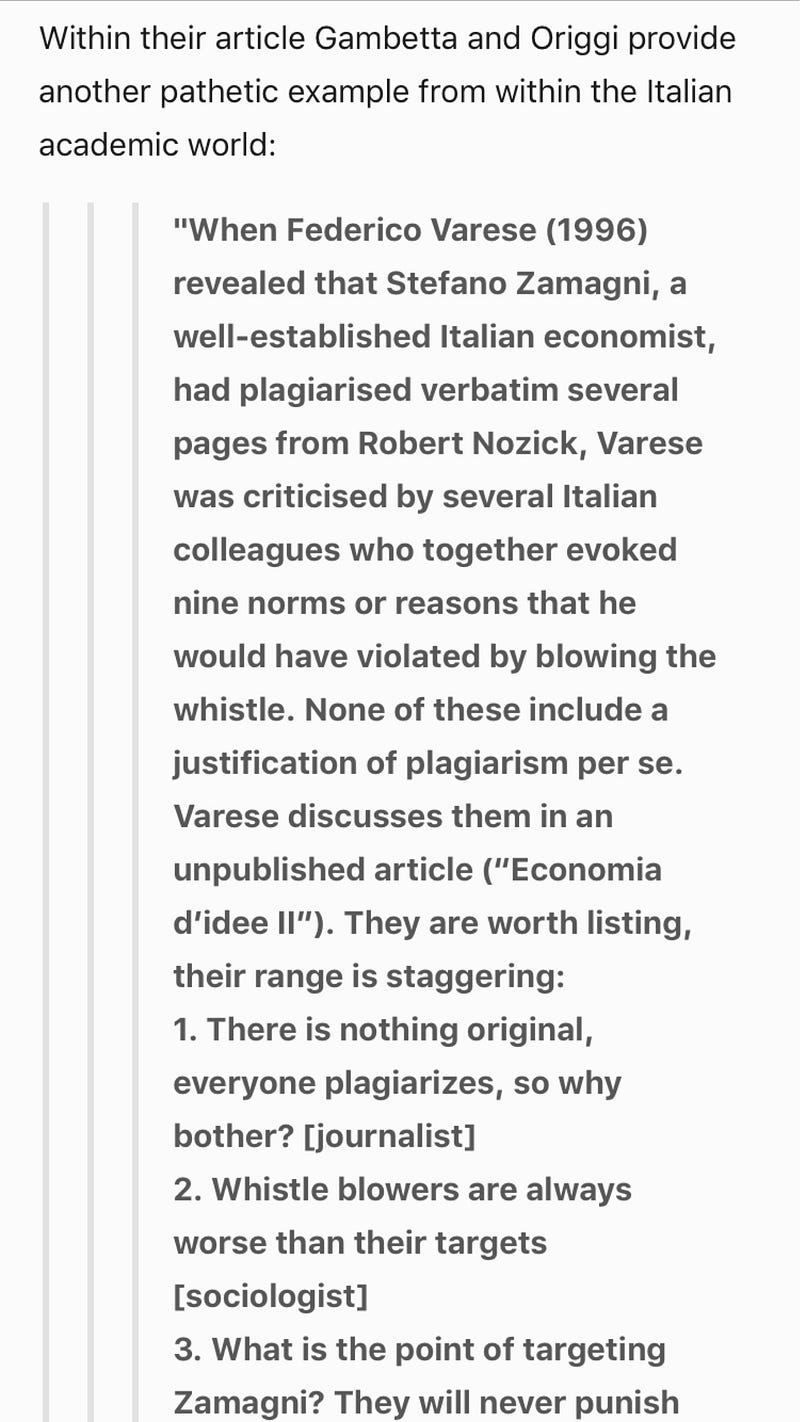

In 2009, they published a journal article called “The LL Game” (available in full here at a $36 cost). Here’s the abstract of their article:

So it turns out that if Nigerians are mad, Italians are mad too.

Let’s not forget that while one can only be mad if one’s behaviour seems strange to somebody else, that alone is not a sufficient condition for diagnosis. Notice how the authors describe a perception of cheating to outsiders, but insiders adapting to and relying on low quality outcomes?

Notice also that there’s no mention of corruption (and no, of course that’s not to say corruption doesn’t exist in Nigeria — that’s a whole other blog post), just self-interested, rational agents preferring and reaching an outcome that’s actually also technically Win-Win at the individual level while minimising effort on both sides.

I tried to buy the full study but it turns out I may not have up to $36 in the bank. Not to worry, Origgi blogs about Kakonomics here, in an article she calls‘Kakonomics, Or The Strange Preference for Low-Quality Outcomes’. Her examples from Italy would be far from out of place in Nigeria.

She explains ‘Kakonomic worlds’ like this:

Standard game-theoretical approaches posit that, whatever people are trading (ideas, services, or goods), each one wants to receive High-quality work from others. Let’s stylize the situation so that goods can be exchanged only at two quality-levels: High and Low.

Kakonomics describes cases where people not only have standard preferences to receive a High-quality good and deliver a Low-quality one (the standard sucker’s payoff) but they actually prefer to deliver a Low-quality good and receive a Low-quality one, that is, they connive on a Low-Low exchange.

Basically, standard game theory is premised on one key assumption: that each party in a trade wants to receive a High quality good/service. When both sides don’t have the same/perfect information, moral hazard creeps in and you are more likely to end up with a sub-optimal outcome, whereby one party gets ‘cheated’ (Win-Lose). If the parties can/would collaborate, both could be better off. Economics assumes all this happens in a competitive environment.

In a Kakonomy, that starting premise is basically wrong. Each of us actually wants, and expects, the Lower quality outcome. Where we collaborate is to pretend to the outside world.

How does that work?

In a Kakonomic exchange the buyer doesn’t mind or care for getting less bang for his buck, for he intends to pay the seller in a less than complete way in some form or another, and the seller will not complain at this because he knows he is somehow selling just poof and not bang.

Fascinating.

It looks like three things are crucial to identifying a kakonomy:

- You and I trust each other to underperform.

Kakonomic worlds are worlds in which people not only live with each other’s laxness, but expect it: I trust you not to keep your promises in full because I want to be free not to keep mine and not to feel bad about it.

2. We are experts at paying lip service or playing to the gallery, but we both know what’s up.

What makes it an interesting and weird case is that, in all kakonomic exchanges, the two parties seem to have a double deal: an official pact in which both declare their intention to exchange at a High-quality level, and a tacit accord whereby discounts are not only allowed but expected. It becomes a form of tacit mutual connivance.

3. We’re both happy with the result

Thus, nobody is free-riding: Kakonomics is regulated by a tacit social norm of discount on quality, a mutual acceptance for a mediocre outcome that satisfies both parties, as long as they go on saying publicly that the exchange is in fact at a High-quality level.

Basically there’s little incentive to actually compete, but we pretend to.

If Nigerians are mad, we are not the only ones.

It’s easy to pick on Italians and Nigerians. But Ugandans seem to be in on this Kakonomics thing too.

Two examples from Nigeria, sorry, I mean Uganda:

1.Ugandan time:

If I were to give a simple example familiar to us in Uganda: you are invited to a meeting where you are told that the meeting will start at ‘exactly’ eleven a.m. yet everyone knows that the meeting will actually start much later; thus everyone connives to arrive later because they accept tardiness as the norm. Although the right words are used, a different lower standard is applied.

2. Exam standards and university degrees:

Cheating is widespread in Ugandan Universities, both in examinations and in the preparation of dissertations. However, there is tacit connivance with the teachers, who set revision questions which will come up in exams, and do not use the recognized plagiarism software ‘Turn it in’ to check for plagiarism (with the exception of International Health Science University, Victoria University, UCU and Uganda Martyrs). This is a low low outcome — the students get certificates and degrees, which are not up to international standards, but the lecturers don’t have to put in much effort.

Eerily familiar, no?

A couple of examples from our brothers and sisters in Italy:

- University lecturers (again…)

Gambetta and Origgi observed the LL game being played at an advanced level in Italian universities. Not only would both parties to an agreement deliver low-quality, but they would insist to each other that they were doing an excellent job, and pronounce themselves delighted with what they had received in return.

For example, a visiting lecturer might agree to deliver a series of eight original seminars and be paid an honorarium of €1,200 in advance. In fact, the payment is six months late and it’s only €750 (some excuse about taxes); meanwhile, the lecturer is mostly on holiday with his family and only gives five lectures, all of which are old hat. Both sides expected as much yet both sides loudly announce they’re delighted with the superb professionalism on show. Meanwhile, they are indeed pleased enough: the faculty has not been embarrassed by some visiting star and retains a larger entertainment budget; the lecturer enjoyed a free holiday without having to do any serious work.

2. Contractors (You and I like to call them ‘artisans’…)

So, for instance, in Italy if you hire a contractor to do some renovation work for you, you can rest assured that either the quality of the work promised or the agreed upon time frame for completion will be broken, sometimes both.

Yet you have no need to worry, because the contractor is not counting on you paying him when you promised you would anyways, take it easy. In the end both parties will be equally happy whatever the outcome and take it all in stride, they have both played the “LL game” and Kakonomics has won the day.

But if everyone’s happy, where’s the harm?

The outcome is Win-Win, and we’ve both gotten what we expected from the trade (even if we pretended to the outside world we had different expectations), so there’s been no cheating or corruption in the strict sense.

But the problem is while you and I have both behaved quite rationally at an individual level, there’s a cost at the societal level (economists call these ‘externalities’), which could be direct, where contracting parties are not necessarily end-users (e.g. in the Italian lecturer example, what about the students?), or indirect in that it pollutes the entire system by ingraining a mindset/culture of mediocrity across business, education, politics, media and creativity over time. It creates an anti-competitive spiral that’s difficult for a society to get out of.

I’m going to completely lift Tim Harford’s words here:

There is something rather charming about a kakonomy at first glance. It can be quite pleasant to relax and be a little bit crappy for a while, and we all know that there is nothing quite so exhausting as a colleague — or, worse, a spouse — who is relentlessly perfect.

But a true kakonomy is collusive, a tacit agreement to be mediocre at someone else’s expense. In the case of many Italian universities, it appears that collusive mediocrity costs Italian students and the Italian taxpayer.

Once a kakocracy has been established, it is likely to endure: recruiters will be careful not to hire anyone who might not only rock the boat but also repair the leaks and fix the outboard motor.

The spectre of kakonomics is a reminder of the importance of things that cannot be measured: the culture of an investment bank, or a university, may matter just as much as the explicit rules.

The Secret Sauce

So if you want to foster a kakonomy, how do you do it?

Tim is silent on that one, but here’s my hypothesis:

Try as much as possible to remove competitive elements from your economy and society. Distort capitalist ideals, embracing socialist politics, collectivist ideologies or rentier capitalism and/or allowing state-led corruption to fester, so that the link between hard work and reward at the individual level is distorted. When the resulting anti-competitive norms, customs, values and ideologies have been disseminated over generations and are deeply-ingrained, and you find yourself left with an economically failing society, step back, admire your good work, then tell the people that they are, in fact, mad for responding to system-wide problems and the very incentives before them.

Selah.

Harsh?

Maybe.

True?

I think there’s probably something to it.

There isn’t much widely available online about the features of (or list of) countries that are generally kakonomies (and no doubt at the market level you could probably find examples in every country), but, after a long-winded anti-socialist, pro-capitalist rant (which, if a little emotional and condescending, for the most part I agree with) one economics blog summarises the problem like this:

When economic incentives and differences are removed from the table, people in general revert to not wanting to do more work than they need to, and especially not more than the other guy next door for exactly the same amount of rewards he’s getting.

The other “motivators” that socialists want to ram down your throat (revolution, downward equality, fatherland, state, or even a welfare state), in the end just don’t cut it in pushing the general populace towards greater excellence. Precisely because they are only collectivist ideals, they say and mean precious little to individuals except maybe for the limited time that propaganda is still producing some effect on them not neutralized by harsh reality. As time goes by and the Utopia fails to materialize (as it always must and will), the individuals lose faith and trust in those synthetic collective “motivators.”

In the end everyone will just accept lower quality exchanges for lower quality goods or services, and they will even start to expect and demand from everyone else exactly the same.

So does #ChangeReallyBeginWithMe?

In a way, yes.

Because there is no system without the actions of individual agents.

But also, no. Not in any meaningful or sustainable way.

Because we have seen for as long as human beings have been alive that we struggle with actualising notions of the collective good, especially where there is no clear individual benefit.

Rather than trying to fight human nature and the result of decades-long socialisation, I think a better strategy might entail respect for the individual, and acknowledgement that this ‘change’ is a task that involves all of us, combined with tangible changes and reforms to system-wide elements, such as the government itself and key institutions, such as NASS, the judiciary and the police force.

Change Begins With Me propaganda isn’t necessarily wrong (as long as things don’t turn sinister and we don’t end up in a police state), it’s just not likely to produce anything lasting or tangible from you or me. So it’s probably just not a great use of money right now.

Long term, a fundamental re-orientation in our national psyche will, in my view, require an overhaul of the tone and culture of our politics and economics (for example putting aside puritanical, centrist ideologies and embracing the importance of merit and a respect for markets).

Nobody said nation-building would be easy.

But I digress.

In summary, there’s a word for ‘Nigerians are mad’, it’s called kakonomics.

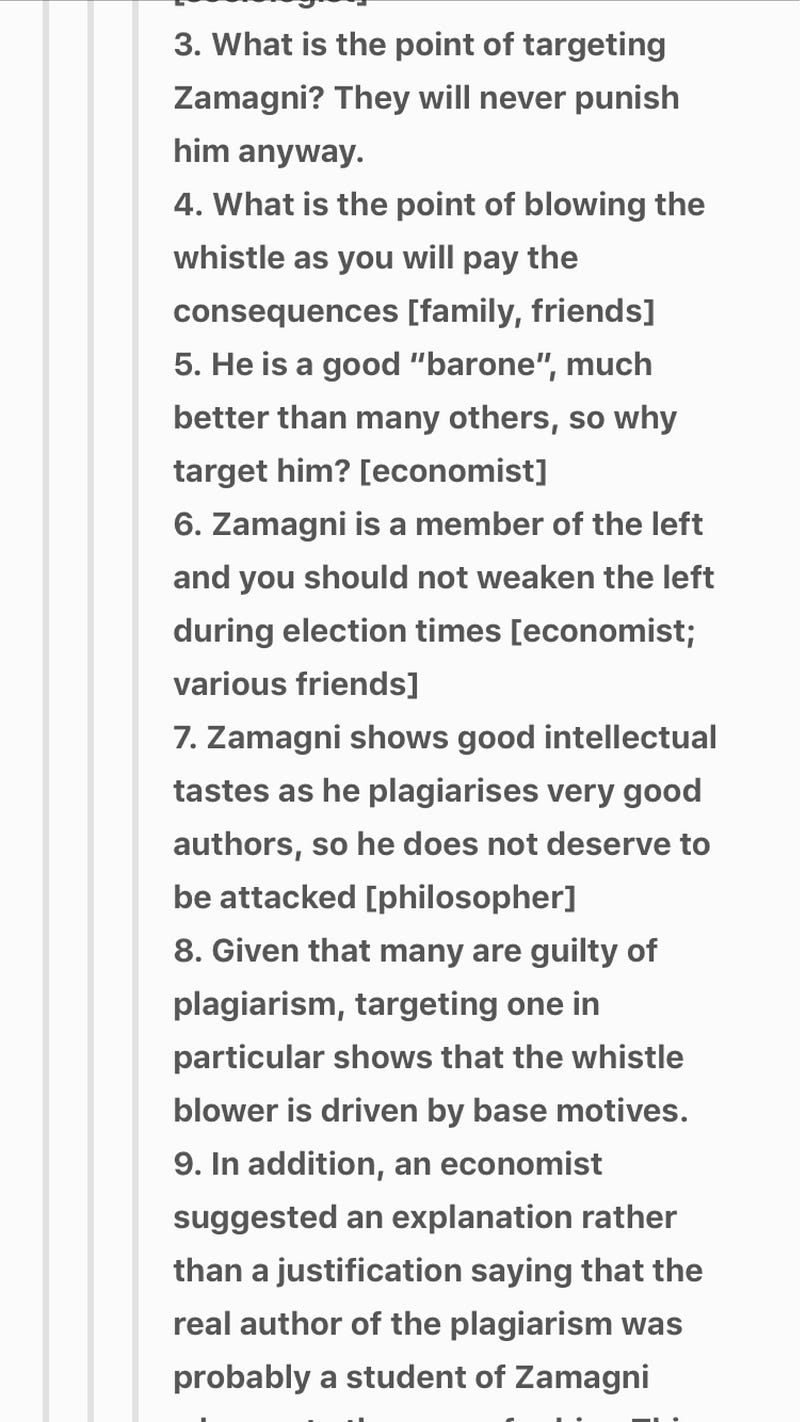

P.S. I found the following example timely and funny, in light of the #ChangeBeginsWithMe Obama plagiarism debacle. You know you’re in a kakonomy when someone tries to remind everyone that corruption is in fact stealing and every inane reason in the book is given from all quarters for why they should keep quiet.

Leave a reply